Pat Fischer was the type of player you’d look at for the first time and say, `No way.’ No way could this pint-sized man start for nearly 17 seasons at cornerback and play at a high level game after game.

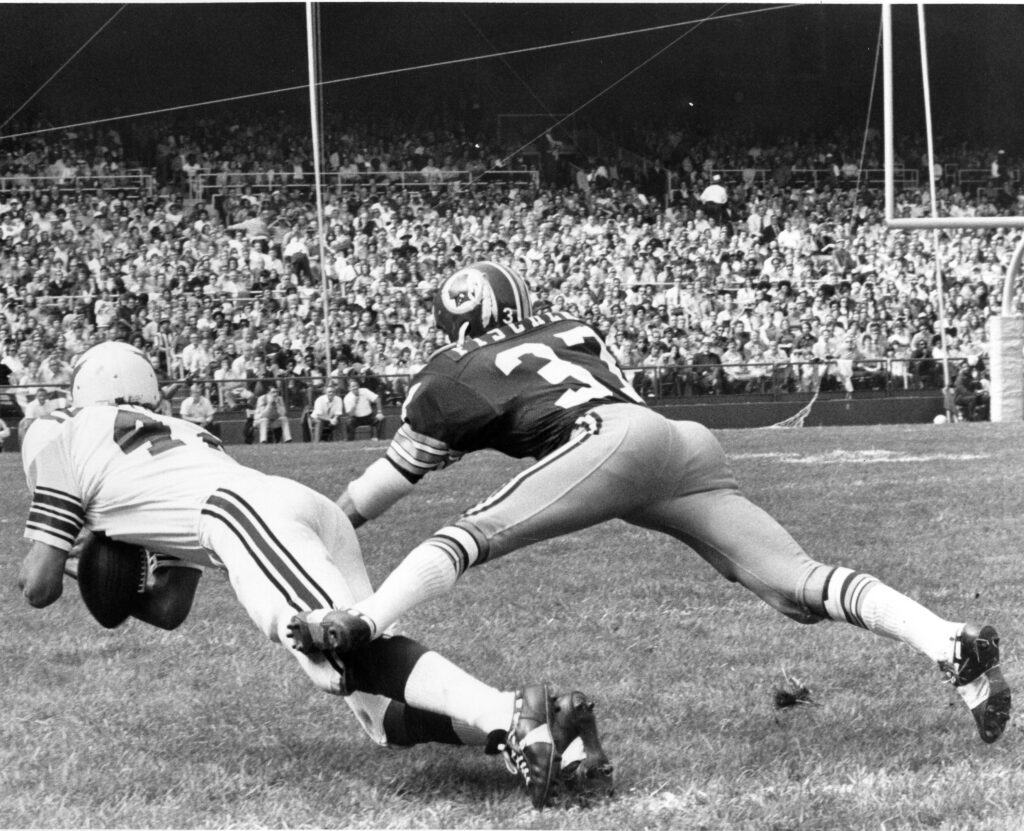

Fischer, listed at 5-9, 170 pounds, was really 169 pounds “soaking wet,” according to one of his Redskin teammates. But he was fearless, never backing down from anyone. Whether it was covering much taller receivers or tackling a 230-pound running back head-on, the tenacious athlete got the job done. He’s widely credited for inventing the bump-and-run defense.

By the time he retired after the 1977 season, Fischer had played cornerback in more games (213) than anyone in NFL history. He intercepted 56 passes, returning four for touchdowns, recovered 15 fumbles and earned multiple Pro Bowl and All-Pro honors. Redskin safety Kenny Houston, a teammate of Fischer’s for five seasons, said he has Hall of Fame credentials.

“He might be the toughest guy pound for pound I ever knew,” said Rusty Tillman, a Redskins special teams star who played with Fischer for eight seasons. “He’d chew that stickum, that stuff you put on your hands to help catch the ball, and you couldn’t even talk to him. If you tried, he was like a rabid dog, `Raaaah.’

“I remember one time, we were playing St. Louis, and the Cardinals ran a sweep, and (offensive lineman) Conrad Dobler pulled out and tried to undercut him. Dobler was one of the dirtiest players in the league. Fischer came up with a handful of mud and just threw it in his face. He was setting the standard right from the get-go: Don’t mess with me. He was afraid of nobody.”

Such feistiness, as Fischer tells it, stemmed from the fact that he grew up with four older brothers who were very athletic and played football at the University of Nebraska. “It might have been that because I was smaller, you had to overcome that with more aggressiveness,” he said. “They demonstrated that, and that’s just how I played.”

Fischer starred at quarterback and halfback at Nebraska, and was drafted in the 17th round by St. Louis in 1961. On the first day of training camp, the diminutive rookie learned there were no helmets or shoulder pads that fit him.

“I just ran up and down the sidelines in shorts for the first few days,” he said. “Then, I went over to the equipment manager at a nearby college, and he gave me a helmet and shoulder pads. Unfortunately, the helmet at the college was purple, and the Cardinals’ helmet was white with a red bird. So I had distinguishing features when I went out on the field.”

Fischer spent his first two seasons mostly returning kicks. But the coaches noticed his effectiveness at cornerback in stopping end runs and tapped him to start at the position in 1963, when he picked off eight passes. The next season, he intercepted a career-high 10 and returned two for TDs, earning Pro Bowl and consensus first-team All-Pro honors. He played three more years in St. Louis, then signed with the Redskins as a free agent in June 1968.

The Redskins hoped Fischer would strengthen a defensive backfield that had just traded safety Paul Krause, now the all-time NFL interception leader. Fischer made the Pro Bowl for the third and final time in 1969 and became a charter member in 1971 of the veteran-dominated “Over The Hill Gang” under new coach George Allen.

Fischer was 31 at the time, the career twilight for many NFL players, and he had a disc removed from his back before the 1972 season. But he persevered on defensive-oriented squads that made the playoffs five times, anchoring the left side of the secondary in an era when defenders could hit receivers all over the field before the ball was in the air. Nicknamed “Mouse,” he was a fan favorite in Washington largely because of his passion and ability to excel in a perceived underdog role. A Washington Star-Daily News headline read: “There’s No Job Too Big For Little (5-9) Fischer.”

Meanwhile, Fischer was busy shutting down receivers who towered over him, one being Eagles 6-8 wideout Harold Carmichael. Fischer was matched against Carmichael whenever the NFC East foes met, and their battles were legendary, with Fischer holding his own against the man who caught 590 passes. “He hated Fischer,” Tillman said of Carmichael.

“It doesn’t matter how tall they are,” Fischer reasoned. “You don’t really have to do anything more than hit a hand or an arm. The question is, can he catch the ball with one hand?”

As for his keys to tackling, Fischer focused on leverage, proper positioning of his weight and balance. Knowing that at his size he was weaker than many ball carriers, he tackled at angles where he made the greatest impact. “He may have been small,” an NFL veteran once said, “but he hit like a son of a gun.”

“Pat Fischer was a neat guy,” NFL Films President Steve Sabol said. “I never knew a player who could explain the science of tackling in terms of geometry. We were doing a film on the hardest hits, and he got into an explanation of leveraging and angles and geometry. It was like being in a mechanical drawing class. When it comes to tackling, you think of putting your shoulder down and knocking some guy’s helmet off. But he had a whole science about what angle, what degree you should hit the guy, how your legs would be bent, when you should explode into him. He wasn’t one of the hardest tacklers but one of the deadliest. He rarely missed.”

Kenny Houston: “He played 17 years, and that’s kind of unheard of for a guy his size. He showed up every Sunday, and I’m thinking, `How can this man do this?’ He was just a tremendous competitor.”